The classical mystery story came to its heyday in the 1920s and 30s. World War I had just ended, and the world was coming through the 1918 flu pandemic that infected a third of the world’s population.

The classical mystery story came to its heyday in the 1920s and 30s. World War I had just ended, and the world was coming through the 1918 flu pandemic that infected a third of the world’s population.

In England, the classic mystery had already been established by Edgar Allen Poe and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The stories showed the reader a very upper society, very proper, with tea being served often. The detective often had a tie to police, but were intellectually superior. They were often given a reluctant acceptance by the local law enforcement officer. Sometimes, the police would call them in because they couldn’t solve the case, but more often the detective burst onto the scene, showing up the helpless officer.

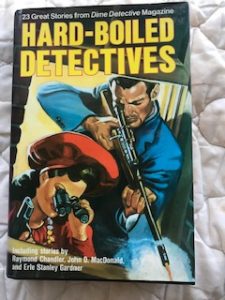

But in America, we saw the emergence of a different type of detective in the hardboiled detective mysteries. In another kind of society, Dashielle Hammett and Raymond Chandler introduced us to the private eye. Often a lone wolf, who tried to dispense his own style of justice in a world with few rules.

[bctt tweet=”The hardboiled American detective was much more cynical than his English counterpart. It wasn’t a game or puzzle to him, but a more personal battle against evil, even of life or death. ” username=”httpstwittercomTimSuddeth”]

Much of America had just lived through a war where more men died of disease caught in the trenches and by gas than by actual combat. The depression was going on with the downfall of the banks and other institutions that had failed in providing the proper safety nets. And Prohibition, where all production, transportation, and sales of alcohol were constitutionally banned, leading to the birth of the bootlegger and public gangster heroes like Al Capone and John Dillinger.

The hardboiled American detective seemed much more cynical than his English counterpart. It wasn’t a game or puzzle to him, but a more personal battle against evil, often of life or death. In the majority of the stories, PI would be beaten, maybe left for dead. Although he could take care of himself on the street, he was always against a superior foe, always the underdog.

Such was the setting and characters of the hard boiled mystery. The stories were darker, more realistic. You could feel the fear, the corruption, and the skepticism of the characters ever seeing justice served.

These stories gave us an everchanging street slang such as gumshoe, dame, jammed, and roscoe. The best stories transport you to the city and streets and you walk along with the PI into this new world with its own rules.

Contrasts between Classical and Hardboiled Mysteries

Settings and Characters

The classical English mystery was set at a genteel, country estate, with just a few witnesses and servants. The families were often upper class. Think about any of the stories by Agatha Christie with Hercule Poirot or Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey.

Another often used setting is that in the small church parrish. Christie’s Miss Marple and the TV show Murder She Wrote. These are set in a small town with limited suspects. A setting where murders just don’t happen.

Unlike the estate or country, the hardboiled mystery is set in a city where you have an infinite number of suspects. Everybody knows everyone and no one. These are not nobles or people of society. They are the society castoffs. If not criminals themselves, they stand just across the line. And they see the gumshoe as their last hope.

Some great examples are Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, Mike Hammer, and Travis McGee. They are not law enforcement officers, often they seem more accustomed to working with the crooks and gangsters than the cops.

POV

Whereas the classical mysteries were often done by a narrator and may have multiple points of view, the hardboiled was almost always written in first person. We experienced the story through the eyes of the PI, getting his thoughts and seeing the events from his perspectives. This made the character the priority instead of the plot.

Tone

There is a decidedly difference in the tones of the two styles. In the classical mystery, we know that they will get the murderer in the end. All the clues and questions will be neatly tied up in a bow, often with the suspects gathered together into one room to hear the detective everything to everyone’s satisfaction. There were some noticeable exceptions, namely The Orient Express and Then There Were None.

In the hardboiled, the little guy usually struggled with those seemingly more in charge, more connected. The PI confronts the guilty suspect but usually the case didn’t end so clean cut. The conclusion rarely saw the hero satisfied.

Hardboiled mysteries have morphed and evolved over the years. It began as a mostly male club in an age that saw women either as something to conquer or trouble to keep away from. Many of the men were quicker with their fists and gin than with their mind.

Over time, especially in the 70s and 80s, the PI became more diverse. Sue Grafton brought us Kinsey Millhone and Sara Paretsky gave us V.I. Warshawski. Walter Moseley introduced LA detective Easy Rawlins and Gary Phillips created Ivan Monk.

Pulp Mysteries

Pulp novels and magazines helped make these early writers and stories available to the public. Printed on cheap paper, and paying the writers very little, these books and magazines filled the newspaper stand, enticing their audience by filling their covers with scantily clothed beauties. Black Mask was one of the most popular.

Many of these early writers have been long forgotten. They didn’t make the paper to last, but to be cheap. Because the magazines paid so little and needed so many stories each week, they often published the stories under a pseudonym. Sometimes, the same writer would have written several stories in the same edition. These cheap books and magazines began to disappear with the shortage of paper during WW II.

The hardboiled detective remains well-represented today. Some of the current authors include Dennis Lehane, Michael Connelly, Elmore Leonard, James Ellroy, and Walter Mosley.

He or she is still someone we can turn to when there seems to be no other way out. No matter what the city’s Chamber of Commerce may try to tell us, those forgotten dark streets where the lone wolf still has a place still exist, whether they are wearing a fedora or a hoodie.

One response to “The Hardboiled Mystery”

[…] wrote about hard-boiled mysteries here. Over on Art of Manliness, Brett and Kaye McKay give us their Top Five Best Hardboiled Novels. The […]