By Tim Suddeth

John le Carré is one of Britain’s most popular spy novelists. In 2008, The London’s Sunday Times listed as 22nd in the fifty greatest British writers since 1945. He has written over 25 novels and a memoir in a career that spanned sixty years, from 1961 to his latest, Silverview, which is being released in October 2021. His books have been nominated for a long list of awards and several have been made into movies including: “The Constant Gardener”, “The Tailor of Panama”, “The Spy Who Came In From the Cold”, and “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy”.

He introduced millions of readers into the secretive world of espionage. Unlike Ian Fleming’s James Bond, le Carré gave us a world that was less glamorous and more morally gray.

Sadly, he died in 2020 of pneumonia. He was 89.

As mysterious as his novels are, they may pale in comparison to le Carré’s real life. If we could only be sure what it was.

Early Life

John le Carré was born David Cornwell in 1931 in Poole, Dorset, England. His mother left her family when he was five. They left him and his brother in the care of his father, Ronnie, who stayed constantly in trouble with the law and his creditors. His family sent Cornwell and his brother to separate boarding schools. More than once, the end of the semester would arrive, and Ronnie hadn’t paid the tuition for the school. His father would take them on vacations to Switzerland, then sneak out without paying the bill.

Ronnie was the epitome of a con man. Married several times, he had numerous affairs, and served time in jail in at least a half-a-dozen countries. Yet jilted lovers, those left to cover his debts, and men who spent time in jail because of him remained enthralled by his personality.

Cornwell became adapt at covering for his father and living in a world where he didn’t belong. For much of his life, his father’s creditors approached him to cover his father’s debts. The difficult father-son relationship became the fodder for his novel, A Perfect Spy, where he based the protagonist, Magnus Pym, on his father. In 1975, when Ronnie died, Cornwell paid for the funeral but did not attend.

Cornwell became disillusioned with the harsh English public-school culture of his day and his strict housemaster, Thomas. He left school early to attend the University of Bern, where he studied foreign languages from 1948 to 1949. In 1950, the National Service called him up to serve in the Intelligence Corps of the British Army. They stationed him in Allied-occupied Austria, where he worked as a German language interrogator of people coming out of the Iron Curtain to the West.

In 1952, he returned to England to study at Lincoln College, Oxford. In 1956, Cornwell graduated with a first class degree in modern languages. He then taught French and German at Eton College for two years

Intelligence Service

Much of Cornwell’ intelligence career is murky, at best. As his writing career grew, he became more reluctant to talk much about what he did. While at Oxford, he worked covertly for the British Service, MI5, spying on for-left groups to locate possible Soviet agents. From an article in the New Yorker, at Eton, he ran agents, conducted interrogations, tapped telephone lines and effected break-ins.

In 1960, Cornwell transferred to MI6, Britain’s foreign-intelligence service, and worked under the cover of Second Secretary at the British Embassy in Bonn.

In 1964, his intelligence career ended when a British agent, Kim Philby, gave secrets to the KGB, including names of British operatives. Cornwell left MI6 and became a full-time writer.

Writing Career

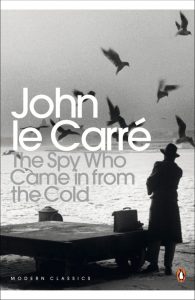

Encouraged by Lord Clanmorris, who crime novels as John Bingham, Cornwell began writing his first novel in 1961. After writing two detective stories, he wrote his first spy novel, “The Spy Who Came In From the Cold”, where he introduces us to George Smiley.

Foreign Office officers were not allowed to publish under their own names, so Cornwell chose the pseudonym, John le Carré.

“The Spy Who Came In From the Cold” became an international best seller. In the postscript to the 50th anniversary of the book, Le Carré wrote, “From the day my novel was published, I realized that now and for ever more I was to be branded as the spy turned writer, rather than as a writer who, like scores of his kind, had a stint in the secret world and written about it. The novel’s merit then—or its offence, depending on where you stood—was not that it was authentic but that it was credible.”

And how strongly his readers believed his stories surprised him. Writing in the Guardian in 2013, he wrote that the British government had vetted the book and approved it as “sheer fiction from start to finish” and determined that it contained no state secrets.

“That was not, however, the view taken by the world’s press which with one voice decided the book was not merely authentic but some kind of revelatory Message From The Other Side, leaving me with nothing to do but sit tight and watch, in a kind of frozen awe, as it climbed the bestseller lost and stuck there, while pundit after pundit heralded it as the real thing.”

What do we really know about John le Carre? @TimSuddeth #openingamystery #authors #mystery Share on XWe have all seen situations where the more you proclaim something to be false, the more people think it is true. Politics and intelligence are the ultimate examples of this. And le Carré had a gift of stating how mundane his actual work in intelligence was, while giving a wink-wink to the listener.

In his obituary in the Washington Post, Matt Schudel recounts the time that a journalist questioned le Carre’s memory of certain events that they witnessed together. Le Carré replied, “Your job is to get things right. Mine is to turn them into good stories.

And good stories are what Cornwell definitely left us.